For those that enjoy listening to music, there is nothing more exciting than exploring and discovering new artists and sounds. This is just as true for professional musicians who are frequently inspired by music from different eras, genres and countries around the world. When the sitar made its way to the West, many popular artists instantly took to its particular sound, and it enjoyed a moment in the spotlight in the late 1960’s. Audiences were exposed to an instrument and culture that they may have never had the opportunity to explore otherwise. The sharing of regional music and one-of-a-kind instruments across cultures only serves to enrich and connect our human experience.

Come along as we take a deep dive into the unique sound of the sitar: India’s most recognized instrument.

Contested Origins

Through the years, historians have often debated over the true story behind the sitar’s origins. The most common tale that is passed along attributes the sitar’s creation to Amir Khusrau,a famous figure in early 14th century Indian cultural history. Apart from being a mystic and scholar, he was also a renowned poet and singer. In the Hindustani classical music of Northern India, he is credited with creating qawwali – devotional singing that still exists today. Another popular theory is that the sitar evolved from the veena, a family of chordophone instruments popular in India. Looking at the design of the sitar side by side with the veena, the similarities are quite evident.

The Sitar’s Essential Knowledge

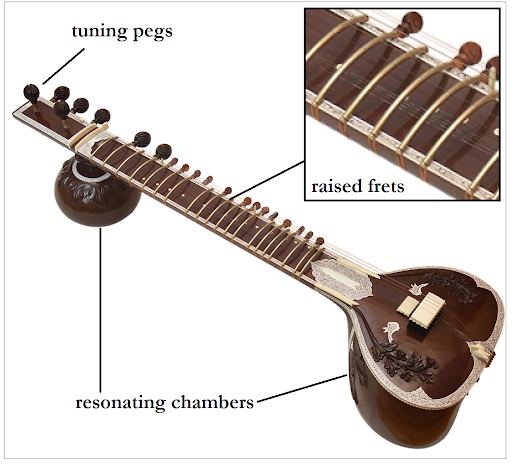

Although the sitar may trace its origins to the veena, it has its own unique features that sets it apart. The word “sitar” may have been derived from the Persian language, meaning “three strings,” although the sitar actually has between 18 and 21 strings. Only six or seven of these strings are actually plucked when played; the rest vibrate when the main strings are plucked. The sympathetic strings help create the unique, lingering sound the sitar is known for. On a guitar, the frets are the raised metal strips that run across the neck of the instrument. On a sitar, these frets are raised higher and can actually be moved around for better tuning.

Many people remark on the sitar’s unique shape, specifically the two rounded chambers on either end. Sitar makers use teak or tun mahogany wood for the long neck and face and dried calabash fruit gourds for the resonating chambers. The Ravi Shankar-style sitars have two round, resonating chambers and are often inlaid with floral or arabesque vine designs. The proper way to play the sitar is from a sitting position, holding it at a 45-degree angle. Traditional sitar players sit cross-legged with the rounded tumba chamber resting on the side of their foot.

Reaching New Audiences

Despite being a staple of India’s Hindustani classical music since the 1300’s, the sitar didn’t become widely recognized abroad until the 20th century. Ravi Shankar (pictured above) is credited for actively sharing the sitar with the world. In 1956, he embarked on a music tour of the West, playing the sitar in live concerts. He drew the attention of David Crosby of The Byrds, fame who connected Shankar with George Harrison, lead guitarist of The Beatles. Harrison became fascinated with the sitar’s sound and incorporated it in songs such as “Norwegian Wood,” “Love You To,” and “Within You Without You.” The pairing of the sitar with the Beatles’ signature acoustic guitar created a blend of East and West unlike anything fans had heard before. Harrison was so enamored by the sitar, he became Shankar’s disciple so that he could learn from the best. Other artists, inspired by the fusion of sounds produced by The Beatles, began incorporating the sitar into their own music.

Between the years 1965 and 1970, the sitar would go on to feature in The Rolling Stones’“Paint it Black,” Traffic’s “Paper Sun,” and Fleetwood Mac’s “Gold Dust Woman,” among many others. The sitar also found a home outside of rock and folk bands, becoming a favorite of many pop acts of the era. The song “San Francisco” by Scott McKenzie, for example, became the anthem of the Anti-War and Flower Power movements, and included th sound of the sitar throughout.

New Horizons: Beyond the 60’s

As the 1970’s began, the sitar craze started to die down. Ravi Shankar, who brought the sitar to the West, won a Grammy Award for his collaborative album with famed violinist, Yehudi Menuhin, titled West Meets East in 1968. Although brief, its years of popularity seemed to cement the sitar’s place as an instrument with global appeal. The invention of an electric version of the sitar further ensured that the Eastern sound remained on the radio airwaves for decades to come. Modern day bands such as Metallica, Pearl Jam, and System Of A Down have used the sitar and its electric version in many of their famous songs.

Once you’ve heard the sitar’s twangy tones, it’s easier to identify its sound in music you likely didn’t register before. Music aficionados, for example, have even noted the sitar in popular video game soundtracks, such as The Legend of Zelda and Shadow Hearts. The sitar’s unique sound adds a distinct Eastern feel to music, perfect for games and films set in places inspired by India. The film Slumdog Millionaire, based on a novel by Indian author Vikas Swarup, was a smash hit when it was released in 2008. The sitar-heavy soundtrack earned top praise around the world, including two Grammy Awards.

The sitar’s success and popularity outside its native India shows us that regional, classical music and instruments can appeal to people in every corner of the world. Foreign instruments and sounds can transport us to other places and teach us about people and cultures that we may be unfamiliar with. It begs the question: should instruments like the sitar be included in and available as part of our arts education? Would learning an instrument categorized as foreign or non-traditional enrich a child’s education in the same way that foreign languages open the window into another culture?