In every field or industry, there are important figures who bring a fresh and unique outlook, and forever change the landscape. Their point of view can often trigger an avalanche of changes and establish lasting legacies. These pioneers are the first to explore new ground and lay the foundation for something new for future generations. For example, Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple Inc., is credited with bringing the company back from the brink of bankruptcy with his forward-thinking approach. Today, his name is synonymous with innovation and success.

In the world of arts education, trailblazers don’t often get this kind of recognition and acclaim, but these innovators exist, nonetheless. In some art circles, Victor D’Amico is considered to be the father of modern arts education. Across a career spanning fifty years, his philosophy on learning arts has had a profound and lasting change. Some might even call him the Steve Jobs of arts education.

Early Life and Education

Victor D’Amico was born in New York in May of 1904 to a large Italian family. His parents were both first generation immigrants whose family came to the United States looking to settle and establish new roots. D’Amico discovered his love for the arts at a young age and pursued that passion in higher education. He studied fine arts for two years in the 1920’s, before switching to arts education. He ultimately earned a Master’s Degree in Arts Education from Columbia University’s Teachers College in 1930.

The Start of a Long Career

In 1937, while he was still studying at the Teachers College, D’Amico joined the Museum of Modern Arts. He became the director of MoMA’s Educational Project, establishing a nearly lifelong collaboration with the famous museum. During his time as the director, he created a number of arts projects that invited people of all ages to participate in them. D’Amico’s radical approach to arts education was emerging, spurred by his belief that art should be accessible across “racial, national and religious differences.”

A New Way of Learning

D’Amico’s most celebrated contribution to the world of arts education was his philosophy that learning art should be a fun and creative process. He wanted arts education to start in early childhood and he rejected the belief that students learned best through constant repetition. Instead, he encouraged a creative, hands-on approach. This style of learning inspired his highly influential program known as The Children’s Art Carnival.

The Magical Art Carnival

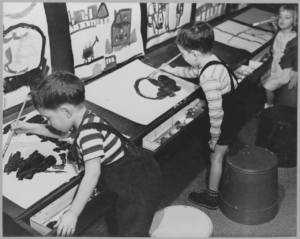

With an exciting name like The Children’s Art Carnival, it’s clear why D’Amico’s early project in arts education became a huge success. His idea was sparked by his desire to create a space of artistic inspiration and freedom. The hour-long experience started with the children walking through a tiny door and stepping into a magical new world.

With colorful walls and music playing in the background, the Carnival was the perfect place to stimulate their young minds. The children’s experience began by playing with toys that were carefully chosen to inspire ideas through a variety of shapes, colors, and forms. They were then taken to a miniature art studio overflowing with art tools and materials. Although it was important to give the children freedom to explore and experiment with art, trained art teachers were always ready to guide them through the process.

The Children’s Art Carnival was so successful that it became an international phenomenon. MoMA presented it in Italy, Spain, Belgium, and India, inviting local children to take part in D’Amico’s exciting art process. By 1969, the Carnival was serving low-income communities in Harlem through The Harlem School of the Arts at no cost to participants. An arts program that was free of charge was almost unheard of at the time, but accessibility was something D’Amico continually promoted as part of his philosophy.

Bringing Art Into the Home

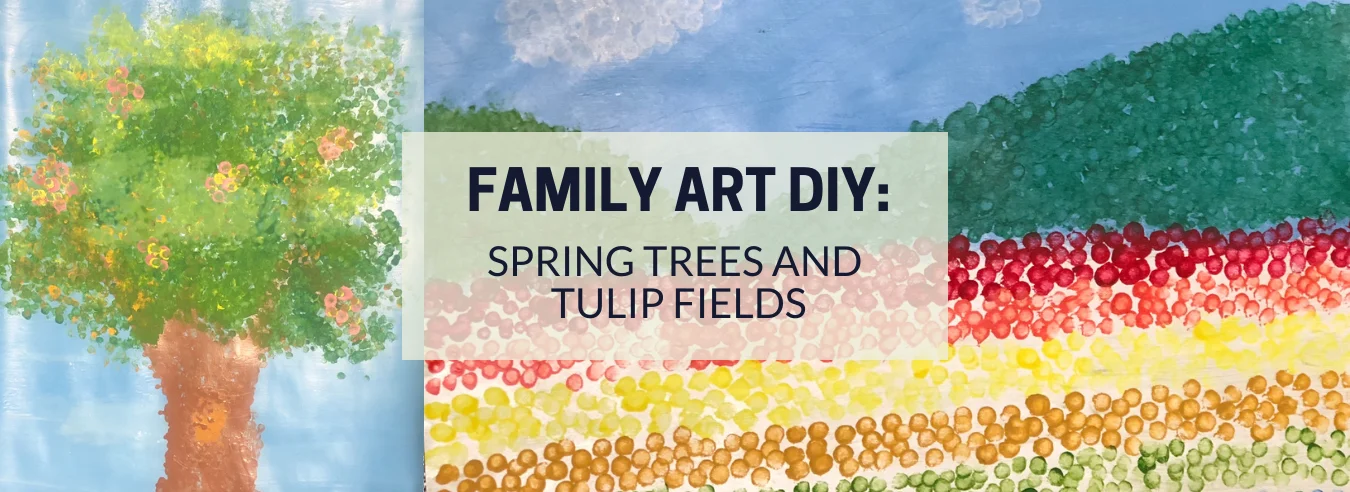

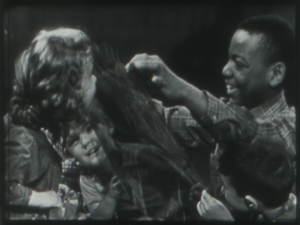

D’Amico also believed that art doesn’t have to start and end in the classroom. In 1954, over a decade after its conception, The Children’s Art Carnival was broadcast on televisions across the country as a new educational program. Through the Enchanted Gate was a recorded version of the art project that had become such a success. In each episode, a group of children, aged anywhere from 3 to 10, explored different aspects of art, such as texture, color, and shape. With the help of art teachers, including Victor D’Amico himself, the children would then work on an art project based on what they had learned. Viewers at home were encouraged to follow along and historians have described this as an early example of “distance learning.”

Through the Enchanted Gate (right)

was an instant hit. During the show’s second season, the “enchanted gate” was opened to family members of all ages, not just children. In each episode, mothers and fathers could be seen working side-by-side with their children. Teachers across the country noticed that their students would often bring art ideas to the classroom they learned from the television program. Parents were delighted to see their children watching a show that enriched their education and encouraged the entire family to create art together. D’Amico saw an opportunity in the emerging technology of television to reach a wider audience and share the importance of art with the world. His innovative combination of art and entertainment would leave a lasting impression in the world of education.

Art for All Ages

Victor D’Amico promoted his “art for all” philosophy both before and after his hit television program. He first put it into practice when he noticed that soldiers coming back from World War II were struggling to adjust to everyday life. MoMA’s Armed Services Program opened up a space to veterans and provided them with art supplies. Together with Abby Rockefeller, who started the program, D’Amico sought to discover “the best and most effective ways to bring about, through art, the readjustment of the veteran to civilian life.” It’s no surprise that the techniques they developed through the Armed Services Program are still being used today.

D’Amico’s vision and creativity knew no bounds, and he saw opportunities to create and share art wherever he went. In 1960, he had an innovative idea to use a World War II Navy barge as a studio and educational space. Anchored on the sands of Napeague Harbor, the barge’s two-story windows offered a 360-degree view of the coastline. At first, the “Art Barge” attracted an older crowd of retirees.; though some were simply looking to fill their day, most were eager to learn from their young teachers. The Art Barge doors were open to everyone,l and soon, people from all walks of life came to experience the teachings for themselves. With classes ranging anywhere from children’s photography, to adult painting, ceramics, and mosaic crafting, there was something for everyone to enjoy.

Victor D’Amico passed away in 1987 at the age of 82. His protégé, Christopher Kohan, had been part of The Art Barge’s collective of artists and teachers for nearly fifteen years by that point. Wanting to keep his mentor’s vision alive, Kohan and the rest of the trustees expanded the art courses they offered and made them even more accessible. Most importantly, Kohan wanted to preserve D’Amico’s philosophy on art education. The Art Barge became a place where artists of all ages learned together. Through interacting and sharing their work, they also learned from each other.

Like his mentor, Kohan believed art had the power to break down social, economic, racial, and gender barriers for the betterment of society. And, most importantly, that anyone, no matter their background, is capable of learning and creating art. This truly was the legacy Victor D’Amico left behind, a legacy that has endured for decades and, hopefully, for many more to come.