With spring in the air, one usually thinks of the flowers and trees in bloom…

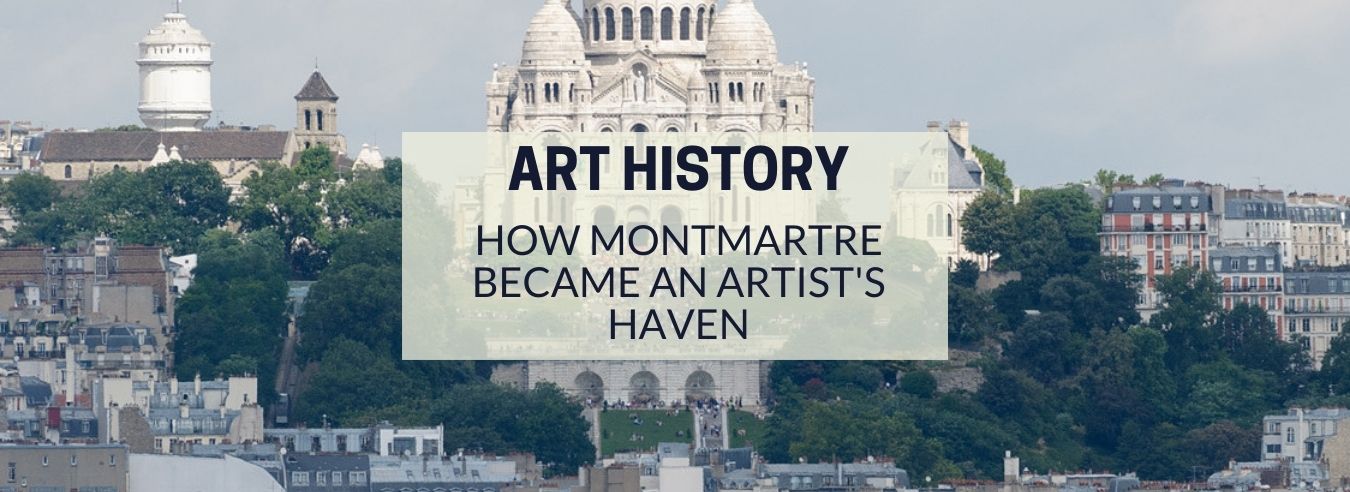

How Montmartre Became an Artist’s Haven

Paris, The City of Light, has a long-standing reputation for being a place of learning and art. The forward-thinking philosophies that the city generated brought society out of the Dark Ages and into the Age of Enlightenment. The multiple artistic movements that flourished within Paris throughout history further cemented its status as a cultural mecca.

Today, Paris is known for its famous art museums, culinary expertise, and diverse city districts. Montmartre is among the city’s most revered arrondissements, or districts, having drawn countless artists to it for generations.

How did Montmartre become the artist’s haven that it’s known for? We’ll look back at the city’s history and the series of circumstances that led to Montmartre becoming the home of artists such as Monet, Van Gogh, and Picasso.

A Brief History

Montmartre began as a small village where Romans once built temples to the God, Mars. The name Montmartre might derive from “mons Martis,” meaning “mountain of Mars.” Geographically, the village was settled on a hill with steep sides and a flat top, commonly known as a butte. The Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Sacré Coeur, stands at the summit of this butte – an area that was once dotted with beautiful windmills. Before Montmartre became the center of art, it was known for its wineries, stone quarries, and gypsum mineral mines. In 1790, the rural village became a commune of the ever-expanding city of Paris. By 1860, Montmartre had become an integral part of the city, and it officially became the 18th arrondissement of Paris.

The Working Class Puts Down Roots

In the late 18th century, Montmartre was quickly becoming urbanized by Paris’ far-reaching influence, however, the small village mentality would not easily be replaced. With low-rent apartments and exemption from city taxes, Montmartre attracted the working class in droves. By the early 1800’s, the country’s intellectuals made their way there, and over time, helped nurture the city’s underground reputation for revolutionary ideas. The working class had been among the most vocal against inequalities since the time of the monarchy and the French Revolution. Those ideas and calls for change lived on in the people of Montmartre. Their fervor bubbled over into what became the first revolutionary uprising of the French Commune. Though the uprising was violently quelled by the French Army, Montmartre became known as a place where free-thinkers could call home.

A Place of Burgeoning Art

The intellectuals and philosophers that made up the core of the French revolutionaries began congregating in Montmartre’s popular cafés. People would gather, drink, and debate the era’s most controversial issues. In 1881, Le Chat Noir, the first-ever cabaret, opened its doors in the heart of Montmartre. Young writers quickly turned it into one of France’s rowdiest and artistically stimulating places of the time. These coffeehouses and cabarets were also frequented by amateur artists who were still making a name for themselves. Montmartre fostered an open and inviting atmosphere, and when coupled with the cheap lodging, it was the perfect place for artists to perfect their craft and find success.

From One Artist to Another

Winding hills, cobbled streets, and quaint cafés greeted the visitors of Montmartre. For artists especially, this romantic destination so full of freedom became highly sought-after. All over France, people spoke of this neighborhood where a Bohemian lifestyle was not only tolerated, but celebrated. In the 1880’s, France flourished in what is known as La Belle Époque, or the Beautiful Era. During this peaceful time before the First World War broke out, France produced countless artistic masterpieces. The city of Paris, and in particular Montmartre, became the epicenter of these artistic endeavors.

Montmartre Becomes the City of Art

As painters such as Renoir invited their artist friends to join them in Montmartre, the neighborhood developed its own unique identity as a gathering place for artists. The lower boulevards where the wealthy lived also housed the art studios of well-established artists. Art supply vendors set up shop there so their favorite patrons had a steady supply of paints and easels. The petits-boulevards higher up on Montmartre’s hill where rent was cheap, attracted the working class and up-and-coming artists like Vincent van Gogh. During his time there, he painted a series on Montmartre and lovingly depicted its famous hills and windmills. With endless inspiration surrounding them, many painters chose the neighborhood as their primary subject. Renoir painted his Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette just outside the famous windmill dance hall. In every corner, art, music, and dance was to be had. People from all over France and abroad came to know Montmartre as a haven for art and entertainment.

Changing Times and Ideas

At the turn of the century, Montmartre’s reputation had reached its peak. With over forty cabarets, dance and music halls, theaters, and circuses, the area was overflowing with talent. The avant-garde style of this live entertainment went boldly against the bourgeois, middle-class sensibilities that dominated the country at the time. As a result, the art of Montmartre attracted people from all social standings and challenged antiquated norms. Upper and middle class patrons often rubbed elbows with working class performers within venues, including the infamous Moulin Rouge, something that was unheard of in French society at the time. Montmartre became a shining example of how art can subvert the status quo and create social change.

Montmartre’s Legacy Lives On

Around the time the First World War broke out, many artists began to set their sights on other places. France was changing, thanks in part to Montmartre, but as a result, the famous arrondissement was no longer the only place artists could express themselves freely. Today, Montmartre and its residents honor the trailblazers in numerous ways. Renoir’s home where he painted many of his famous works became the Montmartre Museum. France designated the 18th arrondissement as a historic site as a way to preserve its beloved history. Montmartre’s history still holds a romantic power over contemporary artists. Today, nearly 300 artists hold license to work on the boulevards, and a ten-year waiting list continuously gets new applicants. Visitors to Montmartre can still find such artists throughout the neighborhood, painting en plein air, just like Monet, Renoir, and van Gogh did long ago.